As the founder of BARC's Rescue from its inception in 2012 until my retirement in 2022, I witnessed the transformation of countless lives, both human and canine. Over the span of a decade, BARC's Rescue became a beacon of hope for abandoned and neglected dogs, providing them with a second chance at life. Through tireless dedication and unwavering commitment, our team worked tirelessly to rescue, rehabilitate, and rehome over 7,000 dogs, each with their own unique story of resilience and redemption. Though my tenure as founder has ended, the legacy of BARC's Rescue lives on, a testament to the enduring impact of compassion and empathy. Today, as I reflect on the journey from inception to retirement, I am filled with gratitude for the opportunity to have made a difference in the lives of so many furry companions and the families who welcomed them with open arms.

The dusty white plane stood out among the gleaming corporate jets, as did its passengers: 26 barking dogs, newly arrived at the private air terminal at Bakersfield, CA.

They had left the shelter that morning with their health certificates taped to their kennels. All week, the staff at Bakersfield Animal Shelter, had been getting them ready, giving them their shots, testing their temperaments, and spaying and neutering as many pups as possible.

On the tarmac, representatives jostled around the animals like vacationers at baggage claim. Penny, a 1-year-old lab mix, is being reassured, “Hi, Pretty, you’re going to go quick!” If past experience is any guide—and transports like this arrive nearly every week all over the country, by plane, truck, and van—they will be gone in a few days, becoming the newest canines living in Canada.

There is not a dog shortage in America—not yet, at least. But there are stark geographic differences in supply and demand. Canada needs more dogs, and California has too many. To compensate, sophisticated dog–relocation networks have sprung up over the past decade, transporting dogs and cats from places with too many to places with too few. Mostly, it’s a tactical problem: “How do we connect those shelters that have too many animals and are at risk of euthanasia simply because they were born there, to those shelters and rescues where these animals are going to fly off the shelves.

These pipelines of adoptable animals—primarily, but not exclusively, moving from south to north—have become a cultural phenomenon in their own right, and a key part of a broader transformation of companion-animal welfare. There are ad hoc bands of volunteers, organizing on Facebook and Petfinder, who cover their back seats with towels and rendezvous at rest stops, passing animals along every couple hundred miles. In big cities and their suburbs, nonprofits have sprung up to partner with overcrowded Southern shelters, hire a driver and load up a van with a few dozen animals every month or more. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many of these groups became overwhelmed with demand in some states, leading to months-long waiting lists and stiff competition among adopters. That spurred a surprising fourth category: veritable smugglers, who saw an opportunity in loading up a horse trailer with the cutest strays and driving north (leaving the nonprofits with the sick and less desirable animals).

It is a good time to be an American dog. In the 1970s, as many as 20 million dogs and cats were euthanized each year. That number has declined precipitously. The ASPCA now estimates 390,000 dogs and 530,000 cats are euthanized each year, down from 2.6 million as recently as 2011. That’s still too many—especially when a way to further reduce the number is at hand. Euthanasia was once seen as an inevitability: there were just too many animals. But a combination of factors—cultural, medical, and political—has changed that. More people want mutts, rebranded “rescues.” Fewer animals are born each year, thanks to broader spay and neuter programs, often dictated by law, and improved surgical techniques. And more are being moved, which helps save those animals, but also opens up space and time to care for others left behind. For shelter staff, who suffer from a disproportionately high rate of mental-health problems, nothing matters more than keeping up with their animals’ needs. Rather than being beaten down by the incessant necessity of euthanizing the unwanted, they are buoyed by a steady flow of adoptions.

Money helps, of course. The geographic disparities that lead one place to have too many dogs and another too few are primarily fueled by a difference in resources. Shelters in heavily populated cities and suburbs benefit from well-funded population-control programs and large pools of potential adopters. Shelters in rural areas struggle with excess animals, and communities with broader economic burdens. The easy problems are nearly solved; the hard ones require a new approach. “Animal relocation” is not only about meeting demand for dogs, but also building the capacity to help all animals.

The ASPCA-sponsored flight exemplifies an organized effort to connect disparate communities in pursuit of a common goal. It is a living, breathing—barking, panting—geographic arbitrage. But by treating these flying puppies as points of connection between communities, like the knots in a net, the issue of excess animals can be addressed. It’s a recognition that some problems, even ones that bridge red states and blue states, can be solved together.

When BARC’s Rescue began working with Bakersfield Animal Shelter, its challenges could be measured with a simple formula. Like many shelters, it calculated its “live-release rate”: the number of animals that left alive, divided by the total number that came in through the door. I remember if we had a cat that sneezed, we didn’t keep the cat. New animals filled the door of the shelter every day, and there was neither the space to house them nor the money to pay the staff to take care of them.

On a crisp California morning with a deep blue sky, Bakersville staff sit in front of two computer monitors inside their office. Think Pawsitive, says the plaque above the desk. Each week, sometimes several times a week, Bakersfield organizes the transports in cooperation with rescues. They start with a blank spreadsheet and begins assembling the manifest, drawing on the animals waiting for their ticket out, or checking in with any of three dozen partner organizations to see who might be “transport eligible.” When they text partners, they reply immediately. If they takes the dogs, it frees up crowded kennels, with the assurance that the animals will go on to a good life. “They’re all pets, they’re just homeless. They just need somewhere to go.

Some come with scars, others with stories. Elmer Fudge, a 1-year-old hound mix, was the largest on the list that day, at 89 lb. He’d arrived a couple weeks earlier as a stray, and the staff now knew him well. “Elmer Fudge is ready to lick your face and smell your yard,” noted the last column of the spreadsheet. The mix is crucial, like a box of bonbons, but sometimes it’s not that easy. Bless their hearts they might all be black and brown.” Joyce, a 3-year-old pit bull mix, is white, and traveling with four of her 10-month-old siblings. “Joyce is a sweet soul,” notes the manifest. “She has been through so much.” Joyce and her siblings were among 19 animals seized from a home where a murder took place. You must try to stay dispassionate. You can’t have favoritism on transport, because you can lose sight of what’s best for the dog, and what’s best for the source shelter, and what’s best all around.”

Sending and receiving organizations develop together the shared procedures to help build connections between the source and destination communities. Rather than well-resourced Northern shelter and rescue workers shaking their heads at the poor treatment of animals by their Southern colleagues, the program gives everyone a better understanding of their shared challenges. When possible, they visit one another. “Have them walk a mile in their shoes, because there’s nothing like that,” says Debra Henkelman Therrien of BARC’s Rescue. “They’re already getting their teeth kicked in, just on what they have to deal with every day.”

They talk about someday putting themselves out of business. The end point would be when a combination of transport and population control balances supply and demand, and animals are no longer euthanized for space in America. The adjacent risk, however, is a shortage of dogs that spurs unsafe puppy breeding. That prospect has some discussing the possibility of shelters in high-demand areas starting their own breeding programs. For those who vividly recall the era of high euthanasia rates—much less those who are still living it—it’s a shocking idea, like a cocktail hour at rehab. But, its proponents argue, encouraging more healthy “American mutts” could be an alternative to allowing commercial puppy breeders to meet the public demand for animals.

The next morning, a crescent moon hangs over the California predawn. The staff gathers around, and checks the paperwork on an iPad and shuffles the printed rabies certificates in plastic sheaths. “All the health certs were good?” they confirm.

Then the dogs start coming. A 20-year-old volunteer cradles Button, a tiny dachshund she’s been fostering at home for 10 days. They had already labeled the crates strapped into the back of the van, determining in advance where each animal would go. Their moves are all choreographed and codified by the Bakersfield Animal Shelter and BARC’ Rescue, from closing the van door while each animal is loaded in, to changing out their surgical gowns and gloves to prevent the spread of any illness. A professor of English at the university who runs her own small rescue, brings over Mo, a 9-month-old Rottweiler mix, who jumps in circles. He transport driver’s fills a red watering can with bottled water, then slips its thin spout through the mesh crate doors, filling each animal’s bowl for the all-day journey.

It’s 26 dogs in total, and also a webbing of ties between communities—in Bakersfield California to Calgary Canada, and wherever the dogs end up. When the truck leaves, Bakersfield has space for 26 new animals. Not for long. “No sooner than we get a couple of kennels open, here comes a newbie!” “There is a door they open somewhere and it’s just like … Who let the dogs out?”

The No Kill Conference held in 2012 in Washington DC at the University of George Washington marked a pivotal moment in the animal welfare movement, igniting a fervent commitment to ending the unnecessary euthanasia of healthy and treatable animals in shelters. At this landmark event, advocates, animal welfare professionals, and community leaders converged to share groundbreaking ideas and strategies aimed at transforming the landscape of sheltering nationwide. Spearheaded by visionaries such as Nathan Winograd, the conference galvanized attendees with its impassioned call to action, inspiring a generation of activists to champion the cause of no-kill sheltering in their own communities. It was here, amidst the hallowed halls of academia, that a powerful movement was born—one rooted in compassion, innovation, and the unwavering belief that every animal deserves a chance at a loving home. From Washington DC, the ripple effects of this historic conference would cascade across the country, shaping the future of animal welfare for years to come.

The Dog Training workshop led by Robert Cabral of Bound Angels in Malibu, California, held at Ventura Animal Services, was a transformative experience for both dogs and their handlers. Robert Cabral's expertise and compassionate approach to dog training empowered participants with invaluable knowledge and techniques to strengthen the bond between humans and their canine companions. Against the picturesque backdrop of Ventura, California, participants immersed themselves in immersive hands-on sessions, learning how to effectively communicate with their dogs and address behavioral challenges with patience and understanding. Robert's dedication to positive reinforcement methods instilled confidence in handlers as they witnessed the remarkable progress of their four-legged friends. Through this workshop, attendees not only gained practical skills but also a profound appreciation for the resilience and intelligence of dogs, reaffirming the profound impact of compassionate training on both ends of the leash.

During my externship after completing my Shelter Management Course at The Stockton Animal Shelter, a facility known for its high euthanasia rate, I was determined to make a difference. Over the course of my time there, I worked tirelessly to rescue over 40 dogs, each one a precious life deserving of a second chance. Through careful coordination and collaboration with my rescue organization in Canada, BARC's Rescue I facilitated the transfer of these dogs to loving homes where they would be cherished and cared for. It was a deeply rewarding experience to witness the transformation of these once-forgotten animals as they embarked on their journey to a brighter future. While the challenges were great, the opportunity to save lives and provide hope to those in need was a humbling reminder of the power of compassion and dedication

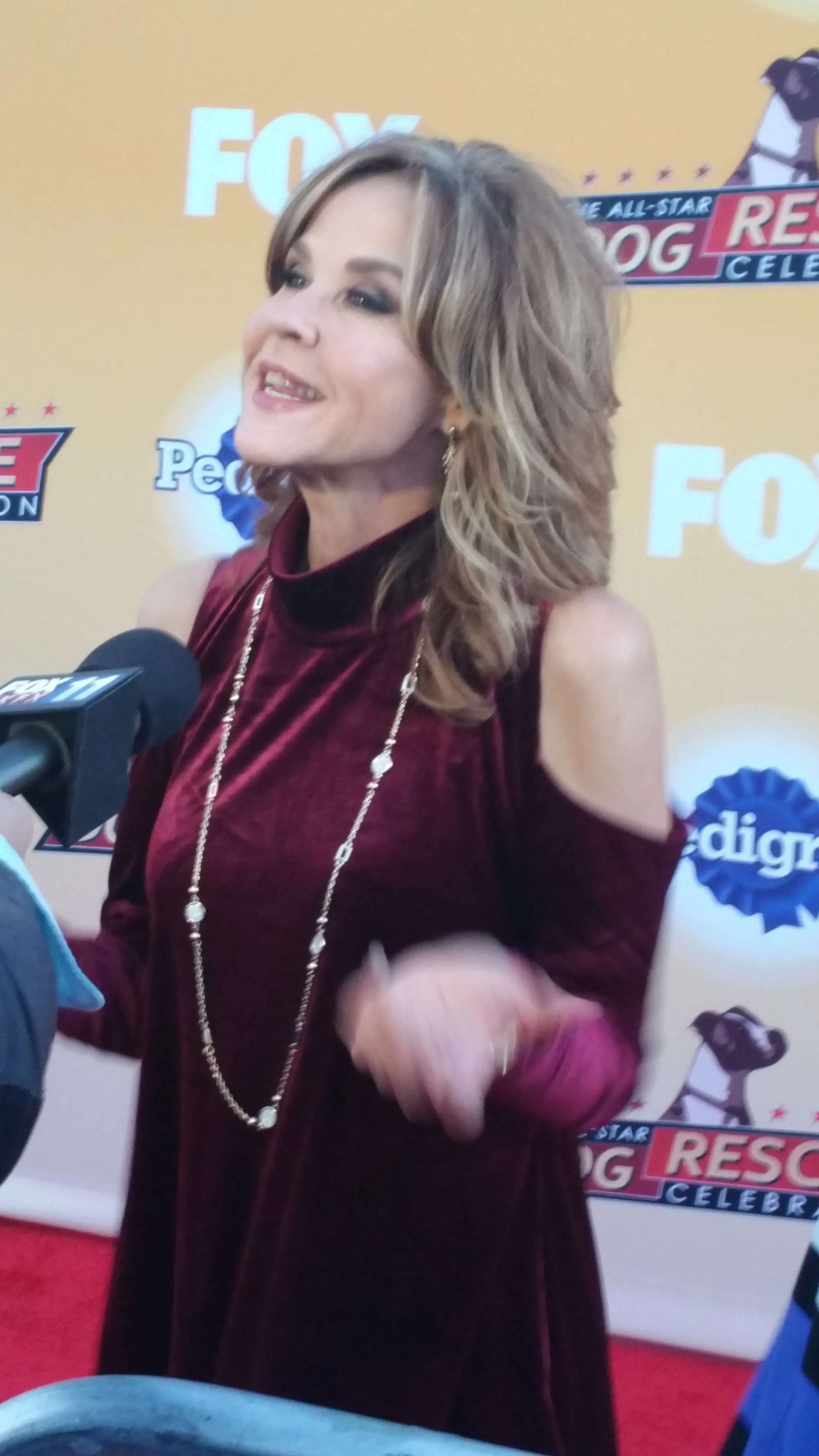

The All Star Dog Rescue Celebration, airing on Fox on American Thanksgiving in 2015, marked an extraordinary day of compassion and hope for countless dogs in need. As the sun rose, the day commenced with a monumental effort to send over 1,000 dogs to safety, including 66 fortunate souls destined for BARCS Rescue. Against this backdrop of rescue and redemption, Hollywood glittered with anticipation as the night unfolded into a surreal experience. Amidst the glitz and glamour, the true stars of the evening shone brightly—the rescue dogs whose journeys from hardship to happiness captured the hearts of millions. The All Star Dog Rescue Celebration was more than just a television event; it was a testament to the power of unity, kindness, and the enduring bond between humans and their beloved canine companions.

During the challenging times of the COVID-19 pandemic in Weed, California, restrictions and safety measures profoundly affected the dining experience. In an effort to comply with regulations and ensure the safety of patrons and staff, local establishments implemented drive-through services as the only option for customers to access food. Despite the inconvenience and the unconventional nature of dining in one's vehicle, residents of Weed adapted to the circumstances with resilience and cooperation. Faced with limited options, they embraced the drive-through approach, recognizing it as a necessary measure to protect public health. In the face of adversity, the community came together, navigating the challenges of the pandemic with flexibility and solidarity..

Rescue work is often a gritty, messy endeavor, fraught with challenges and heartache, but amidst the chaos and tears, there lies an undeniable sense of fulfillment and purpose. The journey of saving lives is not always pretty, but it is always worth it. Each rescued soul, each wagging tail, is a testament to the power of compassion and the resilience of the human spirit. From the darkest of circumstances emerge stories of hope, redemption, and unwavering love. It's in the moments of uncertainty, when the odds seem stacked against us, that our resolve is tested, and our commitment to making a difference shines brightest.

And so, the story continues. Despite the trials and tribulations, the rescue perseveres, fueled by the unwavering dedication of its volunteers and supporters. With each passing day, more lives are touched, more souls are saved. The challenges may be many, but so too are the triumphs. As the rescue grows and evolves, so too does its impact on the community, inspiring others to lend a helping hand and join in the noble cause.

With each rescue, a bond is formed, a connection that transcends words. It's a silent understanding between human and animal, a shared journey of healing and transformation. And though the road may be long and arduous, the destination is always the same – a place of love, safety, and second chances.

In the end, it's not about the challenges we face or the obstacles we overcome. It's about the lives we touch, the hearts we mend, and the difference we make in the world. For in the world of rescue, every life saved is a victory worth celebrating, and every moment of hardship is a reminder of why we do what we do.

Rescue work is a noble endeavor filled with moments of joy and fulfillment, but it also comes with its share of risks and challenges. Sometimes, those risks manifest in the form of physical harm, as was the case for me when I encountered two instances of being bitten and mauled by large, powerful dogs. Despite my best efforts to help these animals in need, I found myself in the grip of their aggression, resulting in two hospital stays. The wounds, both physical and emotional, serve as stark reminders of the dangers inherent in rescue work and the sacrifices often made in the pursuit of saving lives. Yet, even in the face of adversity and pain, the passion and dedication to the cause remain unwavering. These experiences serve as lessons learned, reinforcing the importance of caution, vigilance, and proper safety protocols in the field of animal rescue.